Colonialism vs. Capitalism: When we think of capitalism, visions of bustling stock markets, entrepreneurial freedom, and economic opportunity come to mind. Contrast that with colonialism—marked by conquest, exploitation, and subjugation. Yet, surprisingly, these two seemingly opposite systems were often intertwined in the world’s history. And the marketplaces they created were vastly different in principle, but eerily connected in outcome.

The Origins of Marketplaces: From Barter to Bills of Exchange

Market systems didn’t start with corporations or kings. They began long ago—perhaps as early as 12,000 BC—when early agricultural communities started to barter surplus grain, tools, and livestock. Over millennia, these exchanges evolved. By the Islamic Golden Age (8th to 12th century AD), the foundations of capitalism were already in motion, especially in the Middle East. Traders developed bills of exchange, credit instruments, and partnerships—creating efficient, trust-based commercial networks.

Europeans borrowed liberally from these innovations. By the 15th century, they not only expanded trade—they launched full-fledged colonial conquests.

Capitalism: Competition, Commodities, and Crashes

Capitalism: Competition, Capitalism as we know it—structured around private ownership, free markets, and minimal state interference—truly came into its own during the Industrial Revolution. Labour became a commodity, banking systems matured, and equity markets flourished.

The upside? Explosive growth, innovation, and global trade.

The downside? Boom-and-bust cycles, monopolies, inequality, and crises—like the Great Depression of the 1930s or the Global Financial Crash of 2008.

Capitalism’s strength lies in its dynamism. It rewards initiative and punishes inefficiency. But its weakness lies in its volatility—and its tendency to allow power to concentrate unless regulated.

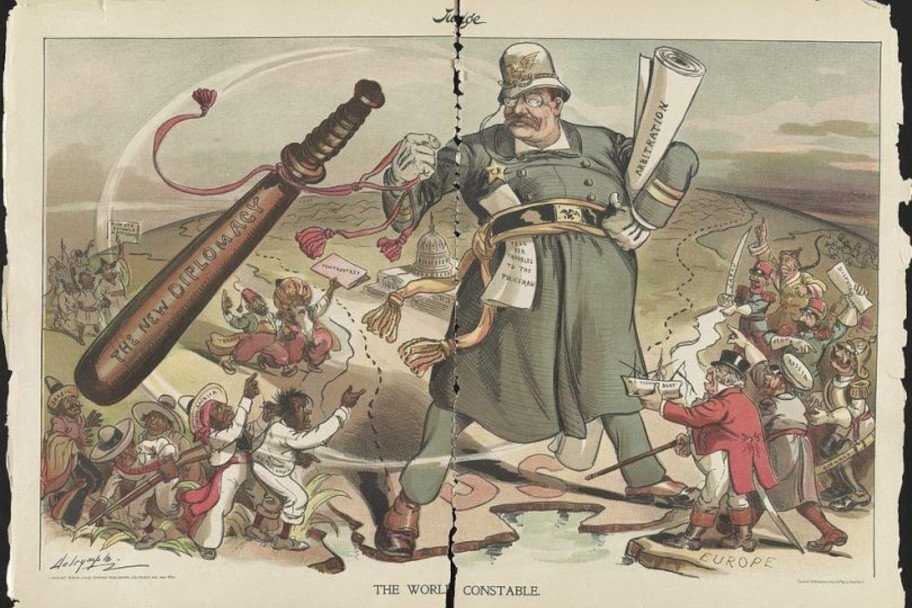

Colonialism: When Markets Serve the Masters

While capitalism prizes free markets, colonialism did the opposite. It imposed controlled markets that served the needs of imperial powers.

European colonisers in Africa, Asia, and the Americas didn’t just rule politically—they rewrote the rules of trade. Local industries were taxed into oblivion. Traditional markets were dismantled. Craft production declined. Colonies were forced to import goods from the mother country and export raw materials in return.

For instance:

- India’s textile industry, once world-famous, was crippled by British policies that favoured Lancashire mills.

- French West Africa saw local goods heavily taxed in favour of French imports.

Colonial marketplaces were not based on supply and demand. They were built on coercion, taxes, and monopoly—and engineered to extract wealth, not to foster local development.

Colonialism: When Markets Serve the Masters

While capitalism prizes free markets, colonialism did the opposite. It imposed controlled markets that served the needs of imperial powers.

European colonisers in Africa, Asia, and the Americas didn’t just rule politically—they rewrote the rules of trade. Local industries were taxed into oblivion. Traditional markets were dismantled. Craft production declined. Colonies were forced to import goods from the mother country and export raw materials in return.

For instance:

- India’s textile industry, once world-famous, was crippled by British policies that favoured Lancashire mills.

- French West Africa saw local goods heavily taxed in favour of French imports.

Colonial marketplaces were not based on supply and demand. They were built on coercion, taxes, and monopoly—and engineered to extract wealth, not to foster local development.

The Irony: Capitalists Practicing Command Economies

Here’s the great paradox. The same European nations that championed capitalism at home—England, France, Holland—imposed something more akin to state socialism in their colonies: price controls, quotas, restricted enterprise, and government monopolies.

Colonial economies were not capitalist marketplaces. They were exploitative constructs where market mechanisms were suspended to serve the geopolitical and economic aims of the empire.

Postcolonial Shadows: Is Neo-Colonialism Alive?

Although formal colonialism ended after World War II, many argue that its logic persists. Global trade rules, intellectual property regimes, and strategic resource extraction today reflect lingering imbalances between rich and formerly colonised nations.

Ironically, the free-market economies of today often operate with subtle remnants of colonial logic—subsidising their own industries, protecting patents, and imposing unfavourable trade conditions on the Global South.

Conclusion: The Marketplace Isn’t Always Free

True capitalist marketplaces are rooted in freedom—freedom to produce, trade, compete, and innovate. Colonialist marketplaces, by contrast, were tools of control and suppression.

Understanding their differences is crucial—not just for historians, but for policymakers, entrepreneurs, and global citizens who believe in equity and inclusion in today’s global economy.